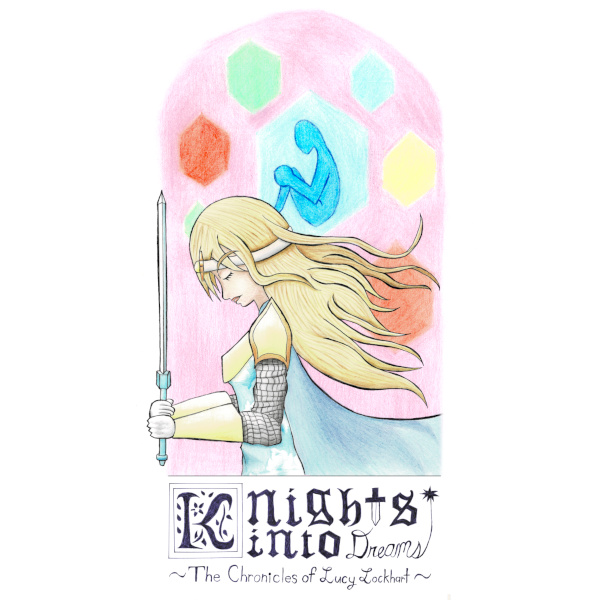

Knights Into Dreams: The Chronicles of Lucy Lockhart

by Marcelle J.J. Padilla

written July 29, 2025

On those nights you fall into a never-ending dream, who lifts you back up to face the day?

Caring too much: the greatest curse in a world where survival means self-interest. Even in the midst of her freshman year of university, Lucy Lockhart knew the people closest to her were quietly falling apart. Yet the days and nights passed with Lucy on a conveyor belt through her own mundane life. As Lucy's circumstances showed her all too well, when school, work, and existential dread at the state of the world have your hands tied, it's easy to drift past the people who need you most, even when they're in arm's reach.

On one fateful night, Lucy doesn't dream—the dream comes to her. Grass surrounds and laughs at her. Ideas and voices come and go of their own accord. The whole world marches to its own rhythm while Lucy is barely a speck on the ground.

But little does she know there is a staircase, out in the middle of all this grass, ascending higher and higher to a place that could grant one's soul the same kind of continuous ascension—as long as one does not fear venturing into dreams.

Below is a first chapter excerpt of an original web novel by me. You can read the full story for free on Royal Road and Scribble Hub!

Imagine awakening not to the soft but solid pressure of a mattress at one’s back, but the coarseness of dirt against against one’s palms and the tickle of grass blades along the fingertips. And when vision swam back into view, it brought with it a bright mid-day sky carrying feelings of disbelief and suspicion—not because there was anything wrong with the sky itself, but rather with the way it had replaced the white painted ceiling of a bedroom with an endless blue tapestry and the drifting pearl foam of clouds. No, that in itself was not strange, for surely there were people in the world, somewhere, who slept and awoke outside.

But of all the people who had wandered onto the mysterious isle of slumber from the ever so great outdoors, not one of them was a Miss Lucy Lockhart with nineteen years to her name.

And so, it came as no surprise that this expanse of idyllic, grassy fields offered only confusion to a Miss Lucy Lockhart meant to awaken to a bedroom, a bedroom housing a desk, a desk topped with textbooks and notebooks and pens, one such pen having written “Notes for the Mid-Term” on a sheet of paper the night before this rude awakening. Could this place be the park down the block? Could this be some kind of practical joke, like that one episode (a fan favourite?) from a particular sitcom (that inescapable sitcom) where a major character awoke to find his bed afloat in a river (cue laugh track)?

Alas, there was no sand-stained swing set, nor cherry-red slide gleaming in the mid-day sun, nor dirt pathways stirred up by barking beagles and tottering toddlers to confirm that yes, this was indeed the park down the block. Or even that this was a park at all. The only park-like thing present was the grass, and the grass certainly wasn’t saying anything to that effect.

Whatever the grass was saying, it likely only said to each other, as there was a whole lot of it. In fact, its sheer uninterrupted abundance would seem to suggest that, somehow, the entire world consisted of nothing but grass. Grass, and the sky above it. Green and blue. Blue and green. Like the pastorial paintings one might see of the summertime prairies, paintings that elicited a sense of fantasy and escapism and wholeness before being brushed back to the back of the mind and then, eventually, oblivion as focus went to schoolwork and family problems and world problems and…so many other things a painting couldn’t fix.

But for as nicely as the grass complimented the still and serene dullness of the sky, those blades of green were cheekier than they looked, for in a certain direction there lay above them something that wasn’t more grass. It was familiar at first sight, and then an illusion, a trick of the light once the finer details were made clear, and then a not-so-small indication that this whole space may not exist within the realm of the waking.

For surely, those awake would never, ever see a floating staircase.

Much less one that reached higher, and higher, and higher, so unceasingly through the sky that a broken neck was a sure thing when one set their gaze to follow it to its end (if it had one). Is this a dream?—might be said by footsteps approaching the staircase in a confused and anxious daze.

And what is the point of asking that?—the staircase might say in its stubborn presence, its refusal to dissolve as a mere mirage or hallucination. There is nowhere else to go, so why not climb me and see?

Thus the grass laughed and cried at being crunched underfoot, but the staircase remained obstinately silent and proud at Lucy climbing up onto its first levitating step. Well, there may have been a slight giggle at the shivers elicited from the coldness of that step’s surface, welcoming bare feet with a Cheshire grin. That step, and all the rest of its kind, shined a proud marble white with a visible tint of baby blue, swallowing up the colour of Lucy’s pyjamas so that, to those higher powers peering down from on high, there was naught but the staircase itself and a small, barely-perceptible speck moving along it.

This staircase was featureless, as most staircases were, for it was the destination rather than the journey that justified their existence (contrary to what clever adages had to say). But unlike most any staircase, this one was so stupendously long and high no mere human gaze could observe the destination. Where, then, does the eye wander when it grows bored of seeing another step, same as the last fifty? Why, it wanders down, down, down, to those lands that this enormous and impossible staircase rose out of and lorded over. Such a thing would be unfortunate for individuals beset by acrophobia, but fortunately the small, timid mouse of a woman who had spent her lifetime shrinking away and was now climbing these steps did not fall into that category of fear. Nor was there any actual falling happening, despite how the gaps between the steps were large enough to afford her downcast gaze a view of the far, far below.

Far, far below, past the grass standing with an effected, almost impossible healthiness and liveliness, barren desert lands stretched out farther than the farthest expanses. So devoid of life it was! And what little remnants littered atop the dunes were signs of life faded: leafless husks of trees, the deep brown tangles of bushes that were no longer bushes, dry sedimented valleys holding only the faintest memory of water. It was, of course, impossible to see the whole world from just this vantage point atop the stairs. But featurelessness and repetition went on and on, chattering their confusing words around the walking young mouse of a woman named Lucy, never revealing any secrets as to where anything else was, nor whether there was anything more out there to begin with.

But these were weak lies, for the infinite desert’s surface soon procured a bizarre configuration of tiny cubes and enormous blocks. The trickery of extreme height and distance obscured it, but with some imagination and some recollection of the real world, the truth became clear: these structures were homes. Either massive, garish mansions with too many floors and too many wings and side houses to count, or dilapidated little shacks threatening to collapse at the smallest gust of desert wind. Their extreme disparity spoke of an intense desire for symmetry, or perhaps balance in a less geometrically-strict sense, at least to the mind of the one continually climbing the stairs far above these exaggerated abodes.

On and on over the relentless desert arose more peculiarities. A big splodge of yellow declared itself, shyly, to be a massive field of wheat. Hurrah!—one might think, until catching sight of the sharp glimmer of silver all around the field, bisecting it a million times in an interlocking grid, trapping the would-be happy wheat in a cage with a massive, complicated lock.

And then there was the gigantic pit where specks of what first appeared to be sand fell, rose up, then fell again, endlessly. Noise from the pit travelled up even as far as the surface of the staircase, and in that noise it was clear that it was not dumb, meaningless sand cursed to fall over and over. The noise was an amalgam of human voices, crying for help, but oddly spoken as if none of them were aware that other people were falling beside them. Lonely screams, cried in unison. Oh, if only the stairs beneath her feet could be given to those doomed to fall again and again.

And when did these stairs come to an end? They had, in their staunch and proud silence, bragged about their sheer length, but the further these steps were travelled, revealing more and more of the unsavoury world below, the longer and larger these stairs appeared to be—or perhaps they made one small Lucy ever and ever smaller. Each step increased in size and in its gap from the previous step, almost as if straining the possibility of making it one step further. The faint promise of reaching a destination still echoed from the unseeable end, but this was challenged by the ever-increasing draw of despair and alarm of the sights far below. For how could one ignore the sight of such a sad, defeated world, even as one has no choice but to continue walking over it?

Eventually, the stale tans and browns of the desert came to an end, replaced sharply with deep bold blue. Water—it lapped up against the boundary of the desert, crashing violently in waves. Deep beneath its all-encompassing blueness was what appeared to be everything the world was missing: other types of structures, people—who weren’t endlessly falling—milling about and speaking to one another, elaborate congregations of wildlife and vegetation. But they were all totally submerged in blue: drowned and unmoving, trapped in frozen time as if a time-halting bomb had gone off in the middle of an ordinary day.

So distracting was the presence of this voracious ocean that the air past the end of the staircase’s final step was pierced through by the sole of a foot. This was where the staircase would have the easiest time claiming victims, sending them hurtling down the now hundreds of feet of empty air. But the end of the staircase was more gracious than all that came before it—for an extra step materialized to catch the foot that would have fallen straight into certain death.

This new final step was quite different from all the other steps, for it went on and on and on—and it became clear that this was not a step of the arduously tall staircase, but a bridge, a wholly separate and more forgiving bridge, laxly stretching forward through the high air until it ended at a massive wooden door.

No, not a mere door, its enormity said. A gate. The gate. To a massive, white, sparkling castle that stood at the end of the bridge.

How did an entire castle stand aloft so very high up in the sky? It would be advisable not to ask, nor to stare too much at the absence of anything beneath the structure, for migraine-inducing confusion was sure to set in, as had almost happened to young Lucy after two or three bewildered steps across the bridge. Even if one were to ask for such an absurd answer out loud, who would answer? For no guards stood at the gate, nor did the windows and turrets reveal the shadowy figures of distant onlookers. It was really so greedy, the gate, being the only thing that appeared vaguely interactable on the castle’s front face, asking—no, commanding that its sole visitor come up close and rap her fist on its mighty wooden surface.

Was it so wise to knock on the gate of an unknown, floating castle? The gate itself did not resist the idea, reverberating with the echo of Lucy’s meek knocking, but nor did it offer encouragement by opening up even a little bit. Still, there was an empathic deepness to its brown wooden timbers, absorbing and understanding the notions of fear and curiosity and just wanting to be away from the sights of the world below, from the sadness the world evoked and the smallness it cast upon gazers like a silent curse. The door was kind, kinder than the staircase, but still it did not yield.

Nor did it speak, so that the only noise was the howling of the wind, free to roar loudly ever so high up in the sky’s domain. There did, eventually, come a different sort of clamour that came from behind the castle: incredibly loud whirring, the rush of things moving rapidly, and the pristine tone of a bell ringing out several times. There, off to the side, were fanciful ships and tiny, distant people on bicycles—all of them floating in the sky with all the naturalness of jellyfish wandering through the sea’s depths—departing from what appeared to be the rear of the castle. They flew out in different directions and slowly descended down into the world below. Some ships and bicycles—and planes, it seemed as well—rose up from the world below and flew toward the castle’s rear. It was a curious detail, but one that sweated the palms and tightened the throat while standing before the castle’s gate, for now this very castle seemed very central, very important, very potent in its ability to make onlookers feel small, even more so than that ostentatious staircase.

“You may come in.”

Despite all the racket of the wind and the ships and the bicycle bells, that voice pierced through it all. Where had it come from? Since it had said to “come in,” it was logical to assume that the speaker was within the castle walls—and yet, the voice itself had come from nowhere and everywhere, approaching from every direction and zeroing in on the single spot of the one hapless listener. How intimidating that must be in its otherworldliness, and yet it did not inspire fear; for the voice spoke not with authority, but hospitality, and the content of the words constituted not a command, but an invitation.

When the last echoes of the voice faded, the large pair of doors making up the castle’s gate swung inward with a slow heaviness. Though this impregnable structure had now opened itself up to passage and scrutiny, this opening revealed precious little besides a stone pathway covered in luxurious red carpet and massive stone columns, the likes of which were typical and told nothing of what lay further in. If you wish to see more, the red carpet might whisper, then follow me, follow me, deeper and deeper inside.

Much like the voice’s words, however, there was nothing that compelled going inside. No guards stood at the open doors, gesturing impatiently to move along. Nor did the doors shake with the threat of closing once more if faced with too much dilly-dallying. The wind itself had also died down, so that there was no danger of a sudden violent gust pushing in those who were still undecided against their will. This, too—this opening of the doors to allow passage into the grandeur within—was nothing more than an invitation, one that could only be accepted by the voluntary movement of putting one foot before the other.

Of course, there was nothing to inhibit such a simple and natural movement, so the question came down to: Was it right to go inside? Surely, a castle as grand and pristine as this had no relation whatsoever to mundane nights holed up inside a tiny bedroom, poring over Psychology textbooks in the hopes that crammed knowledge would translate to a number on a paper, then a number on a digital transcript, then, after several more translations, a number on a paycheque that was just barely larger than the numbers combined from various bills. Big numbers, small life. Surely there was a bigger life that voice had meant to call out to, and stepping into this castle as someone so tiny and inconsequential would only result in being squashed by matters and forces far beyond what one’s agency could afford. Perhaps, then, it was rightful to step aside and allow the real men and women to walk into their rightful chamber.

Yes, yes, this conclusion sounded right, wrapped up in the disarming voice of familiarity, the same voice that made staying buried under blankets in a bedroom sound like ever the right call to make. Waltzing outside, into the world, into the crossfire of conflicting motivations and ideals and causes to care about and stand for, was a sure way to be shrunken and minified, made into a speck of dust blown across the surface of the world. Better to stay in one’s room, under the covers, where at least that stifling warmth did not hurt as much.

But there were no covers to hide under here. The bridge was bare, and cold, and uncomfortable to lie or sit on. And just off its edges was the sheer breadth of the world below, showcasing in all its unapologetic views the dead and barren desert as well as the drowned and submerged ruins lying beneath the overpowering ocean. There was no comfort to be had here, at this threshold between the bridge and the castle. The only promise for reprieve lay in the castle depths, laid bare behind the mighty doors and beckoning for that first step inside. It did not promise that first step would matter, at all, in the grand scheme of things, but it was a step toward something.

And so, the cobblestone echoed with the pitter-patter of the first step taken by Lucy Lockhart.

The red carpet was a welcome change from the cold hardness of stone, feeling warm and softly textured against her soles. It inexplicably drew her forward through the castle’s reception chamber, producing a sure, definite path through an expanse so wide that it would have been easy to get lost—not from twisting corridors or confusing doorways, but from the sheer enormity of it all.

The stone columns were far more massive up close, and even the benches and stands looked several magnitudes larger than anything one would expect in the real world (this was not the real world, clearly). This was only exacerbated by the complete lack of people, making the empty spaces absolute and unbroken and, thus, another large structure all their own. Despite this, the castle interior was very beautiful, in a spotlessly-clean museum sort of fashion. But one could not help but wonder if there were meant to be people crowding around the tables and benches or leaning casually against the pillars in small talk. There was a still, grey loneliness to it all, melding with Lucy’s solitary and silent venture.

The only companion on this venture was the smooth red carpet, and following its regal length led to a large pair of double doors at the opposite end of the chamber. A statue as large as the double doors stood off to one side some dozen or so paces before the doors. It was as pristine and carefully-chiselled as all the pillars around it, yet there was a curious lack of detail, particularly in the face. This made it impossible to tell who this was meant to be a likeness of, but from the rest of the statue’s figure one might suppose this was a woman. But even this was difficult to surmise, for the statue donned some type of heavy clothing—or perhaps it was armour? If that were the case, it couldn’t have been full body armour, as their head and neck were exposed, their long flowing hair out free and swept slightly to one side as if moved by a nonexistent wind. In one hand the statue held a sword, which was raised above their heads and pointing skyward, as if to make their already-large figure even taller.

This certainly did no favours in terms of alleviating Lucy’s rampant feelings of smallness, and yet unlike all the other enormous things she had encountered so far, this statue felt…inspiring, somehow. And, even more strangely, familiar. Were one to peek into the deepest recesses of Lucy’s memory, they would not find anything close to resembling this statue. And yet, if that statue were taken and put somewhere in the young woman’s mind, it would likely snap into place quite readily, like a puzzle piece that had fallen out of the box and blown away by the wind to elsewhere in the world—or, in this case, another world altogether.

As beautiful and arresting as the statue was, it did not deter the red carpet’s subtle but unyielding spell over Lucy’s feet, propelling her to take step after step. Soon the carpet itself came to an end before the large double doors. Presumably, the voice that had called out was behind them, but though Lucy waited there came no second utterance of that voice, nor did the doors open by themselves.

There was no choice, then, but to open the doors by hand.

But these doors, being nearly as large as the gate, were far too expansive and heavy to open simultaneously; opening just one of them would have to do. Even then, the surface of one of the doors easily dwarfed Lucy’s tiny hand, and there quickly came the question of whether something so mighty and important would yield to such a small and ineffectual hand.

And yet, when that door received a simple but firm push from Lucy’s hand, it swung open with a heavy creak far more easily than that hand’s owner could have expected.

But perhaps it had been done by the unseen hands of the wind, for when the door slid open as far as it was able, what lay beyond was the bright blue sky.

It was no understatement to say that this was utterly perplexing, for the castle was absolutely wider than this based on what Lucy had gleaned outside. The reception chamber would have only been a fifth or sixth of the castle’s depth; there was no way, as far as Lucy’s conception of geometry was concerned, for this door to be leading outside.

But the pinpricks of wind from the cold air that dappled along her cheeks and tickled her nose said otherwise, as did the familiar rushing and groaning of the wind. In the middle of this open expanse was a tall figure covered from head to toe in what appeared to be extravagant robes. They were red…then purple…then blue…then yellow…and every colour Lucy could possibly envision, changing hue with every slight shifting of angle in the sunlight and Lucy’s gaze. Yet this was not the most arresting thing about the figure standing there.

And that, quite simply, was because they were not simply standing there, but floating in mid-air.

A look down at the path before Lucy’s feet revealed that there was no such path—nor any walkable surface, for that matter. Free, empty air was all that lay beyond the door’s threshold, promising a sheer drop to the world below, where ocean waves crashed restlessly, eager to swallow up a new meal. Were it not for Lucy’s fortunate lack of acrophobia, this sight would have induced abject terror, the kind that sends the bones unbalanced and muscles twitching, leading perhaps to an unfortunate tumble down hundreds of feet of unguarded air. As it so happened, all that swept over Lucy was a pallor of confusion and uncertainty: surely, this figure, who had to have been the one calling out to her, didn’t intend for her to take a nosedive?

“You have done well, making it thus far.”

It was indeed the same voice that Lucy had heard outside. And despite the fact that he was clearly in the direction ahead of her, their voice—sonorous and carefully enunciated, like a well-spoken man with a great number of years—sounded out from all directions, just as before.

“You may come closer so that we may speak and resolve your confusions,” said the robed man. “If you would like, of course.”

One would expect that a floating man obscured by technicolor robes, with a voice that emanated from every corner of the world, would inspire trepidation or at least apprehensive awe. And yet, there came from him the same inexplicable sense of familiarity, that there was something inexplicably right about Lucy meeting him, here and now, and that speaking with him was an obligation so intrinsic as to almost be like blinking or breathing. Closing the distance for a more proper chat would be Lucy’s next imperative—if only there was a floor or ground or anything solid at her feet.

“If you wish to come speak with me,” said the robed figure, “you needn’t be afraid of a fall. Place your feet where they may, and the clouds will coalesce, becoming the ground that was yet unneeded until your arrival.”

Despite the authority behind his all-encompassing voice, his words sounded far too fanciful to be true. It was easy enough to lift one’s leg, bringing their foot down on where they wished to step to propel themselves forward, but to believe that solid ground would magically spring up? Solid ground made of clouds? And so the end result was Lucy’s leg raised, foot hanging in mid-air, before coming back down to return to its original position.

“What is driving such hesitation?” His question pierced the heavy air, but not because of its tone—which was, rather than offended or scornful, doused in concern and curiosity. “You have seen many bizarre sights, no doubt. Far more bizarre than clouds appearing at one’s feet. Could it be that you are no longer able to believe that flights of fantasy can coexist with yourself?”

Again, it was not the tone of voice that made his words strike potently—this time, it was the sharpness of fact. A staircase reaching up into the sky, a bottomless pit cursed with endless falling, an entire castle floating hundreds of feet in the air: all of these went beyond bizarre and landed squarely in the realm of nonsensical. So why was it so difficult to believe that clouds, ever the tireless sailors of the sky, could come and gather into a pathway for one who needed it? Was it as the robed man had said, that Lucy was incapable of accepting that the laws of reality would bend for her? But he hadn’t said that she was entirely incapable.

“No longer able to…”

The more those four words tumbled about in Lucy’s mind, the more they dredged up ruefulness, and pity, and yearning. It was the opposite feeling from that of the statue in the reception chamber, or of the robed figure himself when Lucy first saw him across the open air. A gap had formed, somewhere, sometime long ago, in the very crux of Lucy’s soul, cracked in and punctured by days, months, and years, of being silenced, corrected, and boxed in to contain all that growth: of imagination, of dreams, of hopes, of anything that was seen as too gnarly and unruly by reality and needed to be trimmed down to size. What point was there believing in such things, if every step taken was for the sake of making enough of a grade or an income?

But this was not reality. The next step wouldn’t lead to the bus stop, nor the employee changing room, nor a bedroom so overused it was losing colour like a deathly overripe fruit. No, this next step would lead across the sky, worlds away from all of that—as long as Lucy believed it so.

And when the empty air was at last filled with her outstretched foot coming down carefully, streams of puffy white swirled in, condensing and solidifying, replacing the weightlessness and emptiness with firm foundation. The step Lucy took was now a step she had taken.

One step, then another, and another, each greeted with cloudy, cumulus circles of ground that formed wherever her feet may land. No matter the change in tempo or stride length, the cloud steps followed her action and hers alone.

When at last the distance to the robed figure was but a mere three or four feet, he said: “Excellent. You have done well, Lucy.”

The foreknowledge of her name would have drawn immediate questions, but the surprise from that was eclipsed by a clearer look at his appearance. From afar, it had seemed as though his face was obscured perhaps by the shadow of a hood, or hidden behind a mask. In truth, he had neither a hood nor a mask, for there was nothing to hide: he bore no face. His head, slowly cycling through colours like his robes, had a blank space where his face would have been. Atop his head was a pointed, golden headpiece that shone brightly in the sun: a crown.

The King…

The words emerged at the forefront of Lucy’s mind then and there, so profusely that she almost spoke them aloud. It was a reasonable conclusion to make, after seeing his crown and extravagant robes, but there was more familiarity laced into those words, not unlike with the statue of the sword-bearing hero or Lucy’s first gaze at this “King” himself. And this was why, despite the immense difference in size between the two, the King towering to at least the same height as that statue, all that this close encounter evoked from Lucy was wide-eyed awe and admiration.

“I am pleased that you recognize me,” he said in his omnipresent voice. “You would often Dream of coming to my audience chamber, just like this, to heed the needs and requests that this World Kingdom required of its champion.”

That was it: this was not their first meeting. Far from it. Although the memory of it was heavily faded, like the fleeting remnants of a dream in the early morning haze, it nevertheless shone brightly in the oft-forgotten abyss of Lucy’s mind, where childhood memories laid. And because of this, embarrassment swept over like a hot, humid wind, bringing with it the realization that Lucy’s mind had immersed her in dreams that truly were from a more naive time.

“Truth be told,” said the King, “I am overjoyed. You have seldom visited for the past many epochs of your life. It is wholesome, then, that you should return here once more for your Final Dream.”

Final Dream?

The two words, on the surface, were perfectly meaningless. On top of that, they had been uttered by someone who was a figment of dreams—a frequent figment with an established history, but a figment nonetheless.

And yet, those words had also stirred something, like a trick wind that began to blow away a dark, perfectly opaque cloud that had hitherto gone completely unnoticed. Since Lucy’s awakening in the fields, a haze had clouded her mind, softly fogging over a sense of time and place and select portions of memory from the real world. There had been no questioning it, for one does not know what one has lost if they do not know they have lost, but now from the gaps there stirred the shadows of an important memory.

And though it was but a shadow, it was terrifying. And like how a child scrambles to their light switch to replace the infinite darkness with the solid limitations of a well-lit room, this shadow of a memory drew Lucy’s mouth to open in panic.

It did not, however, draw out even the slightest hint of a voice, before her mouth, hanging open for a second or two, sank back down into a frown of silence.

“You intended to ask a question, did you not?” The King was, once again, concerned and curious. More so the former, this time. “Why do you stay your voice?”

His words fell on the ears of the girl staring up at him, her mouth still clamped shut. His words had promised, in their sub-text, that asking a question would be met with kindness and understanding, and so there was no need for fear or hesitation. But still the King did not receive even a drawn breath from his only guest.

The question that could have filled the air was far from complicated. It could have been asked simply. And, simply enough, information about this “Final Dream,” and likely other tidbits about its dreamer, would become known.

But what was the point in all that? This was all gibberish from a dream, a sleep-induced fantasy that didn’t matter, cobbled together from the mind of a girl who didn’t matter. Adding a voice to it, drawing forth the energy to care enough to want say anything about it, would only tie the girl to all these things that were immovable and fleeting—and painful. Better to stay quiet, let this all pass over like the sun and clouds and moon on another identical day, and float through the minutes and hours as a ghost with no worldly attachments.

Now that was familiar, more than anything.

The King’s look of concern was halting, especially this close up, but thankfully, turning around and walking back toward the entrance was easy enough, with clouds still propping up Lucy’s every step. Where was there to go after re-entering the castle interior? Out the gate and down the stairs? Back into the fields? It wasn’t ideal, but at least the nondescript clusters of grass blades could cover her up, sink her down into obscurity, while this dream—whatever it was—came to pass. As long as she was away from this place, hanging so vainly over the entire world, with another person casually investigating her every action and whim—as long as those were far away, there ought to be some solace from the sudden and gripping tension.

That wish was granted when, only a few steps later, the castle and the sky faded away—but the monkey’s paw had curled, for from their absence emerged massive sand dunes, blistering winds, and scorching heat. The sandy ground scalded her bare soles and the wind stung her eyes such that her body recoiled and froze, giving up on taking another step before the mind could even process this physical displacement. An endlessly-long silhouette rose up far in the distance: the staircase leading to the castle. And so it was clear that Lucy had been transported to the desert in the world below, far from the King’s relentless insinuations, but also from any semblance of safety.

The bottom of the stairs was just barely visible on the horizon, meaning that the start of it couldn’t be too far off. And reaching the bottom of the stairs meant reaching the grassy fields, for that had been where she was at the start of the climb.

But the unbearable heat and harsh, cutting wind made walking even a few steps seem impossible, let alone to a spot on the horizon. Staying in one place, conserving energy, seemed the most mindful course of action—but even that was thwarted by the constant resistance needed merely to withstand the unforgiving environment. The pain, the suffering here was impossible to shrug off.

And so, rather than the sands swallowing up the little girl that had fallen into their endless maw, their surface was—slowly, painstakingly—marked by her footprints.

The wind picked up into a gale, kicking a torrent of sand into the girl’s face. Stinging, aching, then frantic desperate wiping at the eyes, and opening them again revealed that the empty desert was no more. The endless sands still claimed the earth, but now there loomed buildings in all directions. These were the very ones that could be seen from the staircase: some ostentatiously large and extravagant and rising proud and erect toward the sky, others barely large enough for two occupants and in various states of disrepair, often sinking into the dunes. These two varieties of structures scattered about and intermingled with no sense of separation. This contrast was jarring enough to begin with, and that was exacerbated by the noises they polluted into the air: the larger mansion-like buildings cackled with indulgent laughter, while the smaller shack-like buildings erupted with screams and crying.

It was too much to bear, far too much to be assaulted with in both vision and hearing—and empathy. One could freeze in place from the overwhelming disparity, but that did nothing to drive any of it away.

And so, once again, the sand was marked by tiny footsteps.

And once again, just a short moment later, after the momentary sightlessness of a blink, the present environment disappeared and was replaced. This time it was the jaw-droppingly enormous wheat field, still locked behind a cage done up with an intimidating lock and no key in sight. This, too, was unbearable to merely stand in the presence of, for the iron bars of the prison carried a palpable air of hostility, casting a mean glare of sunlight in every direction.

More footsteps in the sand, and so the process repeated, replacing the wheat cage with the pitch-black darkness of the endless pit and the screams that came with it. The sight and sound of people falling into it over and over again was demoralizing enough, but there came also the sense of being gazed at—a gaze so inexorably bewitching that mindlessness and inaction were transfigured into the compulsive, subconscious urge to walk toward the edge of the abyss. It took far more willpower than the previous times—not least because there was, for some odd but terrifying reason, a sense of comfort in the idea of falling in—but eventually the dunes tracked footprints moving away from the accursed pit.

Another blink, and this time there was no sand to graze at the soles. In fact, everything was different: from the heat beating down from on high, to the thoroughly empty and dry air that gave the cruel wind free reign. All of them had gone, giving way to ice-cold totality that submerged the entire body, shooting up through the nostrils, pouring down the throat and into the lungs to steal away air, breathing, the very ability to live and thrive and exist.

Drowning.

Everything else around here had drowned: buildings, roads, signs, billboards, cars, and bicycles. With the rushing water that had already invaded the body and threatened to claim it, there was no choice in simply staying inactive. One had to step away immediately—but how? There was nowhere to step; trying to do so only resulted in the futile kicking of legs against leagues of water that would never give way.

It was here, in this realization of total defeat, that a pallor of grey calm suddenly diffused all panic and concern. It said that everything else here had drowned, was dead, had ceased to exist, becoming but an unseen, unfelt drop in the inescapable ocean. So perhaps, it said, it was right to stop struggling, to let go and drown in the depths of blue, primordial oblivion.

But something pierced the mollifying grey. It was fear, perhaps, the primitive fear of dying. Or perhaps it was something more. Whatever the case, panic and concern surged back through the body, coalescing into a different kind of calm: that of determination.

There had to be a way out.

Of course, that seemed all but impossible, thousands of leagues beneath the sea with nothing to provide any sort of leverage. But this same kind of impossibility against the rules of the world was familiar—as was the notion of defying it.

That hunch alone was enough to draw forth the sinking girl’s legs, reaching up and forward as if expecting to find a step.

And, hopelessness against hopelessness, it did find a step there waiting for it.

Contact with the step stopped the sinking, righting the body and allowing for another step further up. This, too, materialized a step in the water. And this continued again, and again, and again, reconstructing the once-haughty staircase from the grassy fields into a subservient rite of passage leading surface-ward.

Getting to that surface seemed to be an insurmountably-long trek, even at a brisk run. But the ocean was perhaps not as endless as it had postured itself to be, for only a minute had gone by before there was the rush and splash of emerging from the water into clear, open air.

The stairs didn’t stop there, nor did its climber. Higher and higher it went on, into the sky, reaching up to a familiar and regal structure that floated proudly in mid-air at what seemed to be the very centre of the world.

At last the new staircase came to an end, right at the mouth of the bridge that led to the castle gate. After the rapid displacements and changes of environment, the castle’s completely unchanged and unmoved state of affairs was almost disorienting. The gate was even drawn open still, as if the King’s command to open it had occurred but a second ago.

No invitation was spoken this time, and staying here on the bridge, which was safe at least from the harsher elements of the world below, would have been a perfectly viable decision. Still, the bridge and then the red carpet rung out with the sound of footsteps, for there was no stopping the vaulting momentum that had welled up from the depths of the ocean—from the depths of the self.

The King floated in very nearly the same spot of the audience chamber, and though it would have been impossible to remember, the sun’s and clouds’ positions appeared to be the same, so that time seemed to have stood still. The King observed silently as tiny clouds formed and disappeared in the empty air, supporting yet more ceaseless steps, approaching ceaselessly until they were within speaking distance.

“Magnificent,” the King said. There was no haughtiness nor condescension in his voice, but such a simple world of consolation did nothing to address the hellish ordeals on the way to his chamber, instead igniting a spark of frustration.

“To provide some clarification,” said the King, “what you just went through was not my doing. It was not a punishment, nor a test. What manifested was a subconscious reaction to your own conscious state of mind.”

As those words flooded every direction, the spark of frustration extinguished, the wind dying down with it so that near-silence remained. The King’s claim was bold, but did not feel untrue.

“You were brought to all those troubled corners of the world,” the King continued, “where simply remaining inactive was not an option. And yet, despite the overwhelming suffering at every turn, you moved forward. You chose to move forward. Even in the ocean’s depths, where there was no ground to follow, you willed into existence your own foundation, and your own way out. Do you understand why you were able to take such monumental actions, despite being—no, feeling so small?”

Drops fell through the open air, sparkling bright in the sunlight, so that they drew attention despite their tiny forms. These drops could not have come from a rain cloud, for the sky in the audience chamber could not have been clearer. No, these were the kind of drops that spilled from the eyes, travelling down the cheeks, seen glittering in the air before they are felt.

They were the tears that fall in anticipation to a cutting answer before it is spoken.

“You are not small,” said the King. “You are not inconsequential. Deep in your heart, you know this to be true. So I implore you: raise your head, Lucy Lockhart, and stop erasing yourself from every sentence and subject of your story.”

The few drops of tears had turned into rivulets, gathering in the eyes and turning the audience chamber into a blurry watercolour painting, so that they had to be wiped away until at last they ceased to flow. Shame came afterwards, scalding and scornful, but there was no strike to be felt, no reprimand to hear. There was only the gentle breeze, the surreal but beautiful sights of the castle and the King’s robes, and the gentle but solid foundation of the clouds conjured at her feet. Nothing was urging her to hurry up, nor demanding she move out of the way. All of it waited for her—and it was decided that she would wait for herself no longer.

Lucy stepped forward, conjuring clouds into an entire platform beneath her feet.

She looked up at the King and opened her mouth, feeling the wind course through her entire being, stirring in her heart, overflowing with sentiment in her throat.

And at last, she spoke:

“What did you mean by ‘Final Dream?’”

What will be the answer to Lucy's question? And where will she go from here? Read the rest of the story on Royal Road or Scribble Hub!